A US perspective on the current and future

regulation of anticoccidial drugs and vaccines

Paul Duquette, Phibro Animal Health (paul.duquette@pahc.com)

65 Challenger Road, Third Floor

Ridgefield Park, New Jersey 07660 - USA

Abstract

The US broiler industry is currently thriving, with more than 8.5 billion

broilers produced per year. This success is partly due to the availability of

multiple anticoccidial drugs, both chemicals and polyether ionophores, and

anticoccidial vaccines. In the US, the Center for Veterinary Medicine (CVM),

Food and Drug Administration, is responsible for approval of new anticoccidial

drugs, while the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) is responsible

for approval of anticoccidial vaccines. The CVM anticoccidial drug approval

process is quite rigorous, requiring demonstration of manufacturing capability,

efficacy, target animal safety, human food safety, and environmental safety. The

USDA approval process for anticoccidial vaccines, which differs somewhat from

the CVM approval process, also requires demonstration of manufacturing

capability, efficacy and safety. Although many anticoccidial drugs are currently

available (and expected to remain available), few, if any, new drugs are under

development, due to the high cost and length of the approval process. Only a few

anticoccidial vaccines are currently available, but new vaccines are under

development. The US and worldwide broiler industry should continue to thrive as

long as currently used anticoccidial drugs are used prudently, anticoccidial

vaccines are used when and where effective, and necrotic enteritis and other

diseases that exacerbate coccidiosis are controlled.

Introduction

The broiler industry in the US is currently a thriving industry. US broiler

producers currently produce more than of 8.5 billion broilers per year. The

industry relies on various feed additives, including growth promotants used to

enhance productivity and maintain the health status of the animals, therapeutic

antibiotics used for disease treatment, and anticoccidials. Without these

products, all of which are approved by FDA after extensive testing to

demonstrate efficacy and safety, it would be impossible for the industry to

maintain the quality of its products and to survive in its current form.

In order to understand the current and future of the industry in general, and

anticoccidials in particular, it is important to have a historical perspective.

History of the

US broiler industry and anticoccidials

In his campaign for the presidency in 1928, Herbert Hoover used a campaign

slogan “a chicken in every pot and a car in every garage”. Hoover’s intent

was to promise affluence to the US public. However, his slogan gives an

important perspective regarding the broiler industry. In 1928, only the

affluent, or farmers who grew their own, could afford to eat chicken, which was

considered a “high priced” protein source. Although numbers for broiler

production aren’t available for 1928, they are available beginning in 1940. In

1940, 143 million broilers were raised for consumption in the US. This number

grew to 631 million in 1950, 1.8 billion in 1960, 3 billion in 1970, 4 billion

in 1980, 5.8 billion in 1990 and 8.3 billion in 2000, and reached over 8.8

billion in 2004. During this time period, average live weight of broilers

increased from 3 pounds to over 5 pounds, feed conversion decreased from 4

pounds of feed per pound of broiler to under 2 pounds, mortality decreased from

10% to 5%, and market age decreased from 12 to less than 7 weeks. [Note that the

production data listed above was obtained from various United States Department

of Agriculture (USDA) publications. For more information on the US poultry

industry, see the USDA web site at http://www.ams.usda.gov.]

The tremendous improvements in the broiler industry can be attributed to many

factors. Intensive breeding programs have resulted in highly improved genetics.

Management practices include knowledge of nutrient requirements and improved

feedstuffs. Antibiotic feed additives, especially those that control necrotic

enteritis, allow for intensive rearing conditions with reduced mortality, while

growth promotants improve feed efficiency and growth rate.

Of course, without anticoccidial drugs and vaccines, the growth of the US

broiler industry described above would have been impossible, as coccidia are

ubiquitous and extremely deleterious to the growth and survival of broilers.

Fortunately, introduction of the sulfur/sulfonimide drugs in the 1930s started

an era of treating and preventing coccidiosis. Since that time, the emphasis has

been on prevention, with the introduction of the chemical anticoccidial drugs in

the 1940s through 1970s, introduction of the first polyether ionophores in the

1970s, and the more recent introduction of anticoccidial vaccines (although

vaccines have been used in broiler breeders since the 1950s, formulations for

broiler production are relatively new). Growth of the US broiler industry

demonstrates a high correlation with the discovery of new anticoccidials.

The current status of anticoccidials and anticoccidial regulation in the US

Anticoccidial drugs and vaccines are regulated by two US agencies. The Center

for Veterinary Medicine (CVM), Food and Drug Administration (FDA), regulates

anticoccidial drugs, while the United States Department of Agriculure (USDA)

regulates anticoccidial vaccines. As such, they will be discussed separately,

below.

Anticoccidial drugs

The US Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act mandates that a new animal drug may not be

sold in interstate commerce unless it is the subject of a New Animal Drug

Application (NADA). In order to obtain an NADA, a drug product sponsor must

demonstrate that the drug is safe and effective, and can be manufactured in a

manner that preserves its identity, strength, purity and quality. The Center for

Veterinary Medicine (CVM), Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is responsible for

the review and approval of NADAs. See U.S. Code: Title 21-Food and Drugs Part

514 – New Animal Drug Applications at

http://www.access.gpo.gov/nara/cfr/waisidx_98/21cfr514_98.html for more

information on the NADA process.

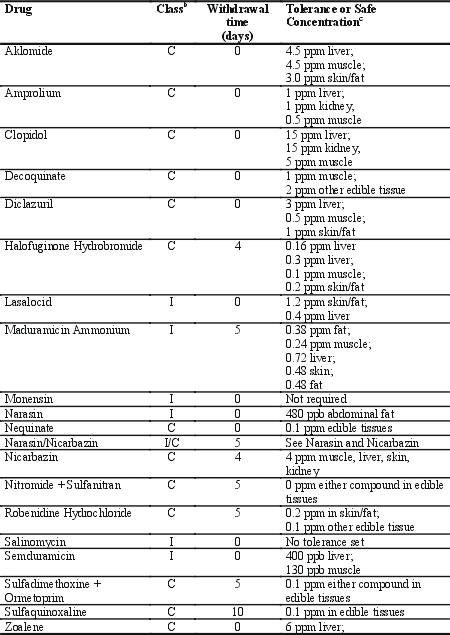

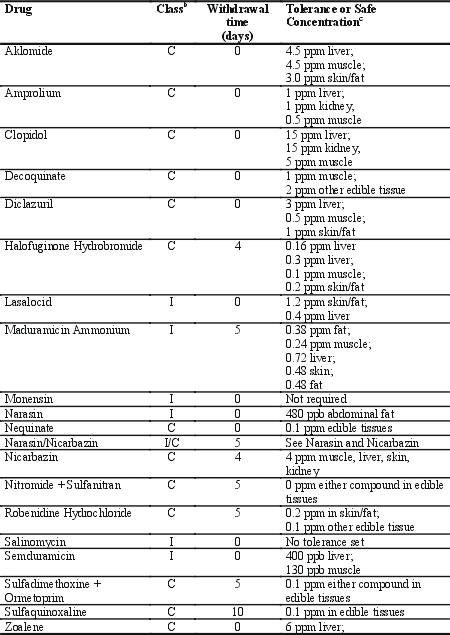

Twenty anticoccidial drugs/drug combinations are currently codified (approved)

for use in broilers in the US. Table 1 lists the approved US anticoccidial

drugs, their approved withdrawal time, and their tissue tolerances/safe

concentrations.

Table 1. Anticoccidial drugs approved for use in broilers in the US.a

A Data from United States Code of Federal

regulations, 21 CFR Parts 556 (tolerances) and 558 (approvals and withdrawal

times), 2005. For further information, see

http://www.gpoaccess.gov/cfr/index.html.

b C = chemical; I = polyether ionophore.

c US FDA sets tissue tolerances and/or safe concentrations, which may differ

from European MRLs. Tolerance refers to a concentration of a marker residue in

the target tissue selected to monitor for total residues of the drug in the

target animal, and safe concentrations refers to the concentrations of total

residues considered safe in edible tissues. Tolerances are shown in normal font,

while safe concentrations are shown in italics. In cases where no safe

concentration is listed separately, the tolerance is the safe concentration.

Although all of the drugs listed in

Table 1 are approved, many of them are no longer marketed.

The US CVM approval process for animal health drugs used in food animal species

(including anticoccidial drugs) is quite rigorous and comprehensive. Submissions

for approval can be phased (each “technical section” submitted separately)

or complete (all “technical sections” submitted simultaneously). For further

information on phased submissions, see Guidance for Industry (GFI) #132 located

on the CVM website at http://www.fda.gov/cvm/Documents/dguide132.doc]; for

further information on complete submissions, see GFI #41

http://www.fda.gov/cvm/Guidance/Guideline41.htm). Whichever submission format is

chosen, the following technical sections are required:

· Chemistry, Manufacturing, and Controls

· Effectiveness

· Target Animal Safety

· Human Food Safety

· Environmental Impact

· Labeling

· Freedom of Information Summary

· “All other information”

Each of these sections will be discussed briefly.

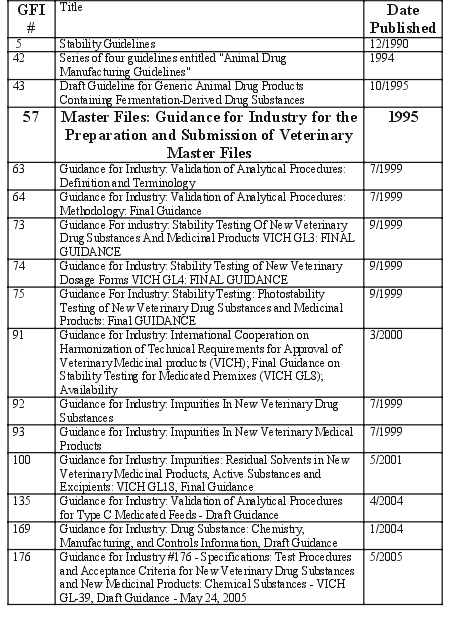

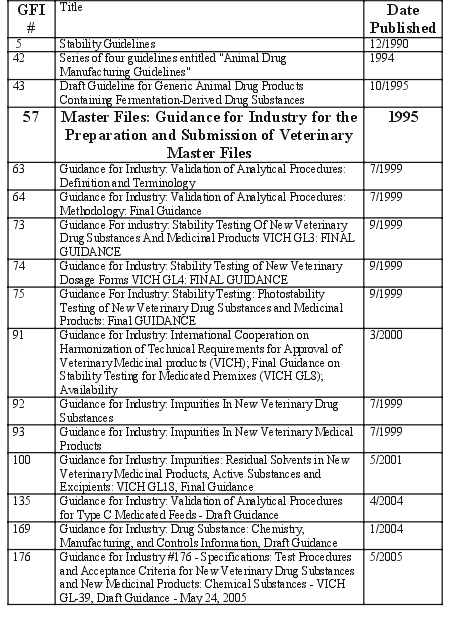

The Chemistry, Manufacturing, and

Controls (CMC) section should contain complete information regarding the

manufacture of the new animal drug active ingredient and the new animal drug

product. It should contain information on personnel, facilities, components and

composition, manufacturing procedures, analytical specifications and methods,

control procedures, stability, containers and closures, Good Manufacturing

Practice (GMP) compliance, and other aspects of the chemistry and manufacturing

processes. CVM has published multiple GFIs that describe different aspects of

the CMC section process, including those listed in Table 2.

Table 2. CVM Guidance on Chemistry, Manufacturing and Controls.a

a All CVM GFI can be found on the CVM

website at

http://www.fda.gov/cvm/guidance/published.htm.

The Effectiveness section must contain full reports

of all studies that show whether or not the new animal drug is effective for its

intended use. CVM has published Guidance for Industry (GFI) that specifically

outlines the studies necessary to demonstrate effectiveness of anticoccidial

drugs. Specific studies described in this GFI include battery studies (with both

single Eimeria species and mixed cultures), floor pen challenge studies, and

field trials. For further information, see GFI #40, at:

http://www.fda.gov/cvm/Guidance/dguide40.pdf.

The Target Animal Safety technical section must contain full reports of all

studies that show whether or not the new animal drug is safe to the target

species. In addition, any target animal safety issues that become apparent in

efficacy studies must be reported in this section. Target animal safety study

design for poultry anticoccidial drugs is specifically mentioned in section IX

of GFI # 33, located at:

http://www.fda.gov/cvm/Guidance/Guideline33.htm.

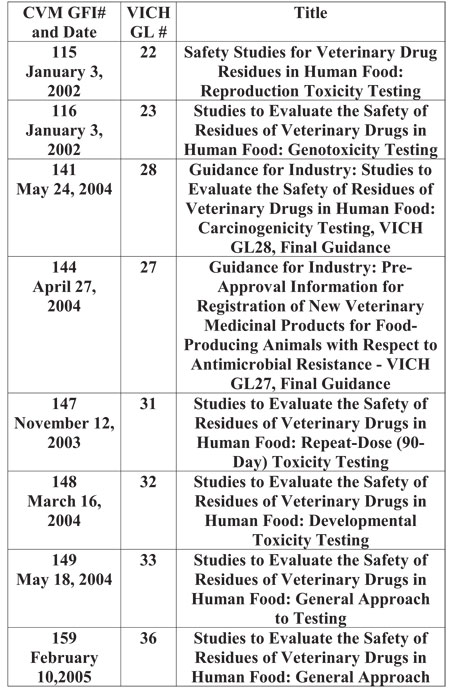

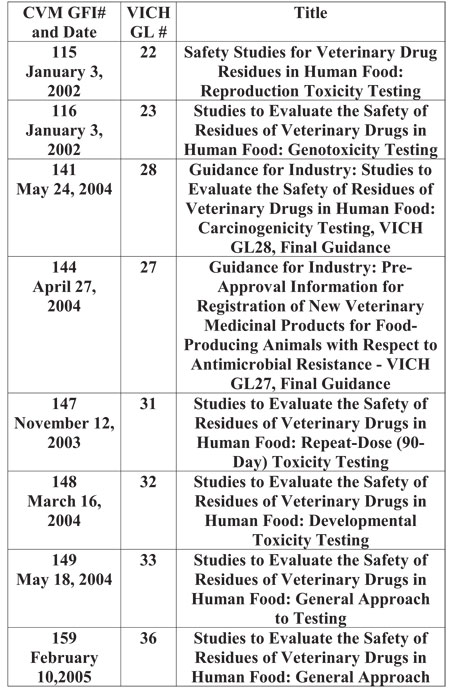

The Human Food Safety technical section is the most comprehensive technical

section, and must contain information on residue toxicology, residue chemistry,

residue analytical methods, pharmacokinetics and bioavailability. CVM has

recently (June 2005) updated GFI #3, General Principles for Evaluating the

Safety of Compounds Used in Food-Producing Animals, including references to the

following Guidelines: Guidance for Metabolism Studies and for Selection of

Residues for Toxicological Testing; Guidance for Toxicological Testing; Guidance

for Establishing a Safe Concentration; Guidance for Approval of a Method of

Analysis for Residues; Guidance for Establishing a Withdrawal Period; Guidance

for New Animal Drugs and Food Additives Derived from a Fermentation; and

Guidance for the Human Food Safety Evaluation of Bound Residues Derived from

Carcinogenic New Animal Drugs. In addition, CVM has adopted various guidelines

(GL) developed by the International Cooperation on Harmonisation of Technical

Requirements for Registration of Veterinary Medicinal Products (VICH) regarding

safety studies for residues, including those listed in Table 3.

Table 3. VICH safety study guidelines adopted by CVM.a

a These guidelines are available on the CVM

http://www.fda.gov/cvm/guidance/published.htm.

It should be noted that, for anticoccidial compounds

that have anti-infective properties (such as the polyether ionophores), CVM has

recently begun requiring studies on microbiology, including the effects of

residues on human intestinal microflora (GFI #159) and evaluation of the safety

with regard to their microbiological effects on bacteria of human health concern

antimicrobial resistance (GFI #152). GFI #152, which describes a

“qualitative” approach to antibacterial resistance risk assessment, may be

superceded by a more “quantitative” approach. Although no examples of a

quantitative risk assessment are available for the polyether ionophores, CVM has

published a draft risk assessment on virginiamycin, a product used in poultry to

control necrotic enteritis and improve growth rate and feed efficiency. The CVM

document:

(http://www.fda.gov/cvm/Documents/SREF_RA_FinalDraft.pdf) demonstrates the CVM

approach to risk assessment (and also demonstrates that the continued use of

virginiamycin poses no significant risk to human health).

The Environmental Impact section must, by regulation, contain either an

environmental assessment (EA), or a request for categorical exclusion. A claim

of categorical exclusion must include a statement of compliance with the

categorical exclusion criteria and must state that to the sponsor’s knowledge,

no extraordinary circumstances exist. “Environmental Impact Considerations”

and directions for preparing an EA can be found in 21 CFR Part 25. In addition,

CVM has adopted 2 VICH environmental guidelines, GL6 [CVM GFI #89 Guidance for

Industry - Environmental Impact Assessments (EIA's) For Veterinary Medicinal

Products (VMP's) - Phase I, http://www.fda.gov/cvm/Guidance/guide89.doc] and

GL38 [GFI #166 Draft Guidance for Industry - Environmental Impact Assessments

(EIA's) for Veterinary Medicinal Products (VMP's) - Phase II:

http://www.fda.gov/cvm/Guidance/dguide166.doc].

The Labeling section should include facsimile copies of container labels,

package inserts and any other labeling that will be used with the products. For

medicated feeds, copies of representative labeling for the Type B and Type C

medicated feeds, referred to as “Blue Bird” labeling, should also be

included. Facsimile labeling is nearly final labeling that adequately reproduces

the package size (actual or to scale); graphics; pictures; type size, font, and

color of text; and the substance of the text to demonstrate to the reviewing

Division that the final printed labeling will be in compliance with applicable

regulations. Labeling should address any user safety concerns identified during

the review process. CVM has not published final guidance on labeling; however,

labeling requirements are codified in 21 CFR Part 201:

(http://www.access.gpo.gov/nara/cfr/waisidx_98/21cfr201_98.html).

The completed Freedom of Information Summary (FOI) Summary should include the

specific language relevant to a technical section that was agreed upon during

the review of the individual technical section (e.g., the tolerance and

withdrawal time for a new animal drug intended for use in food-producing

animals) and should be accepted by the Division responsible for the evaluation

of the target animal safety technical section. For further information on FOI

summaries, see GFI # 16 (FOI Summary Guideline,

http://www.fda.gov/cvm/Guidance/Guideline16.htm).

The All Other Information section must

include all other information, not included in any of the other technical

sections, that is pertinent to an evaluation of the safety or effectiveness of

the new animal drug for which approval is sought. All other information

includes, but is not limited to, any information derived from other marketing

(domestic or foreign) and favorable and unfavorable reports in the scientific

literature.

It should be noted that, in the US, anticoccidial drugs cannot be used in

combination with any other drugs until the combination is approved by CVM (see

CVM Guidelines for Drug Combinations for Use in Animals, GFI # 24, at

http://www.fda.gov/cvm/Guidance/Guideline24.htm.

For further information on the animal drug approval process in the US, visit the

CVM website and associated links at:

http://www.fda.gov/cvm/nadaappr.htm.

Anticoccidial

vaccines

The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) is authorized, under the 1913

Virus-Serum-Toxin Act (see http://www.aphis.usda.gov/vs/cvb/vsta.htm) as amended

by the 1985 Food Security Act, to ensure that all veterinary biologics produced

in, or imported into, the United States are not worthless, contaminated,

dangerous, or harmful. Federal law prohibits the shipment of veterinary

biologics unless they are manufactured in compliance with regulations contained

in Title 9 of the Code of Federal Regulations, Parts 101 to 118. Veterinary

biologics for commercial use must be produced at a USDA-approved establishment,

and be demonstrated to be pure, safe, potent, and efficacious.

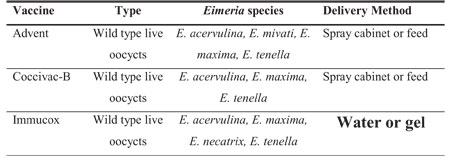

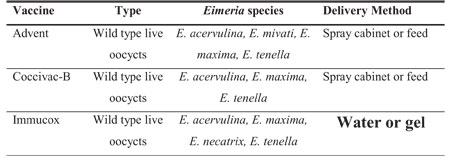

Three anticoccidial vaccines (Table 4) are currently USDA approved for use in

broilers in the US.

Table 4. Anticoccidial vaccines

approved for use in broilers in the US.a

Note in the above table that all currently approved

vaccines contain wild type live oocysts, but vary in the Eimeria species they

contain and their delivery method.

The USDA vaccine approval process is outlined as follows (see

http://www.aphis.usda.gov/vs/cvb/lpd/lpdfaqs.htm):

In order to manufacture and sell veterinary biologics in the US, domestic

manufacturers are required to possess a valid U.S. Veterinary Biologics

Establishment License and an individual U.S. Veterinary Biologics Product

License for each product produced for sale.

Foreign manufacturers of veterinary biologics may export veterinary biologics to

the United States, provided that the manufacturer's legal representative

(permittee) residing in the United States possesses a valid U.S. Veterinary

Biological Product Permit to import these products for general distribution and

sale.

The following documentation must be submitted to USDA for a biologics

establishment license:

· Application for United States Veterinary Biologics Establishment License

· Articles of Incorporation for

applicant and any subsidiaries if a corporation

· Water quality statement

· An application for at least one United States Veterinary Biological Product

License

· Personnel Qualifications Statement for supervisory personnel

· Blueprints, plot plans, and legends

The following documentation must be

submitted to USDA for a biologics product license:

· Application for a United States Veterinary Biological Product License

· Outline of Production and, if applicable, Special Outlines

· Master Seed data, including test results for purity, safety, identity, and

genetic characterization

· Master Cell Stock data, including test results for purity and identity

· Product safety data from laboratory animal and contained host animal studies

· Host animal immunogenicity/efficacy data

· Field safety data

· Labels for all containers, cartons, and enclosures (circulars)

· Potency test validation data, including correlation with host animal efficacy

3 consecutively produced pre-license serials that have tested satisfactorily for

purity, safety, and potency

Guidelines (Veterinary Services

Memorandums) on preparation and submission of the above information can be found

at the USDA website, http://www.aphis.usda.gov/vs/cvb/vsmemos.htm.

In addition to the approved vaccines listed in Table 2, vaccines may be produced

and used without USDA approval, provided that:

· The product was manufactured by veterinarians and intended solely for use

with their clients' animals under a veterinarian-client-patient relationship.

· The product was manufactured by individuals or companies for use only in

their own animals.

· The product was manufactured in States with USDA-approved veterinary

biologics regulatory programs, for sale only in those States.

The future of

anticoccidials and anticoccidial regulation in the US

The Animal Health Institute (AHI) has recently published a news release entitled

“Antibiotic Use in Animals Rises in 2004” (see

http://www.ahi.org/mediaCenter/documents/Antibioticuse2004.pdf) that shows that

ionophore/arsenical (grouped to abide by disclosure agreements) sales in the US

increased from 8,644,638 pounds in 2003 to 9,444,107 pounds in 2004. At first

glance, this appears to be good news for the animal health industry; however,

these data demonstrate increased reliance on existing compounds, as no new

compounds have been approved in the past few years. In fact, the last new

anticoccidial drug approval in the US occurred in 1999, when diclazuril was

approved. Prior to diclazuril, semduramicin was approved in 1994. The approval

of new anticoccidial drugs has come to a standstill due to the high cost and

length of time it takes for approval with the current approval requirements:

estimates are that it currently costs more than $25 million and at least 10

years to obtain CVM approval of a new anticoccidial drug (information based on

AHI sponsor input). Industry information suggests that no new anticoccidial

drugs are under development. The good news is that currently marketed

anticoccidial drugs will remain on the market, as there is no indication that

CVM has any concerns with these compounds.

If no new anticoccidial drugs will become available, what will happen to the US

and worldwide broiler industry? It appears that new anticoccidial vaccine

technology may fill some of the void. Dalloul and Lillehoj (2005) have recently

published a paper describing functional genomic technology and recent advances

in live and recombinant vaccine development that may result in broiler

vaccination strategies that work better than current vaccines. Bedrnik (2004)

reviews information on multiple anticoccidial vaccines that have been or are

being developed worldwide. MacDougald et al. (2005) have recently patented

vaccine for coccidiosis in chickens prepared from four attenuated Eimeria

species: E. acervulina, E. maxima, E. mitis and E. tenella (see

http://www.uspto.gov/ patent number 6,908,620). Industry sources suggest that at

least 4 new anticoccidial vaccines are currently under development for the US

market.

However, anticoccidial vaccines are not the complete answer as they are not

always effective and do nothing to control necrotic enteritis, and anticoccidial

drugs must continue to be used. The broiler industry must use these products

prudently to avoid over use and possible resistance issues. Shuttle programs

must be adopted to “rest” popular anticoccidial drugs. Both chemical and

polyether ionophore anticoccidial drugs should be used as seasonal conditions

and coccidial challenge allow. Efforts should be made to control necrotic

enteritis and other disease conditions that may exacerbate coccidiosis.

The US and worldwide broiler industry should continue to thrive as long as

currently used anticoccidial drugs are used prudently, anticoccidial vaccines

are used when and where effective, and necrotic enteritis and other diseases

that exacerbate coccidiosis are controlled. The anticoccidial drugs are amongst

the most important tools that allow the broiler producer to produce healthy

birds, because they are the safest and most effective method to control

coccidiosis. In turn, the consumer benefits through low-priced, high-quality

animal protein produced using drugs that have been proven safe and effective in

rigorous scientific studies.

References

[Note: much of the information presented in this paper was gathered from

official US government websites, which have been referenced throughout this

document. Key websites used, and referenced publications, are listed below.]

Websites

United States Department of Agriculture, Agriculture Marketing Service at

http://www.ams.usda.gov

United States Code of Federal

regulations, 21 CFR Parts 556 (tolerances) and 558 (approvals and withdrawal

times), 2005 at:

http://www.gpoaccess.gov/cfr/index.html

United States Food and Drug

Administration, Center for Veterinary Medicine guidance documents at

http://www.fda.gov/cvm/guidance/published.htm

United States Department of Agriculture,

Center for Veterinary Biologics, Veterinary Services Memorandums (guidance

documents) at:

http://www.aphis.usda.gov/vs/cvb/vsmemos.htm

United States Patent and Trademark

Office at http://www.uspto.gov/

Animal Health Institute at

http://www.ahi.org/

Publications

Bedrnik, P., 2004. Control of Poultry Coccidiosis in

the 21st Century. Praxis veterinaria 52 (1-2):49 – 54.

Dalloul, R.A. and H.S. Lillehoj,

2005. Recent Advances in Immunemodulation and Vaccination Strategies Against

Coccidiosis. Avian Diseases 49:1-8.